Avigdor Arikha

Le thème de l’été de la Revue Eclipse est l’Assignifiant, d’où les différents entretiens en lien avec cette thématique et, d’où, cet article sur la démarche picturale et les réflexions d’Avigdor Arikha tirées du recueil Peinture et Regard (Peinture et regard : Écrits sur l’art, 1965-2009, Paris, Éditions Hermann, 2011).

Avigdor Arikha est né 1929 à Rădăuți en Roumanie et décédé en 2010. On connaît ses œuvres picturales ainsi que ses gravures, mais ses écrits, nombreux, sont moins connus. Pourtant, ils sont riches à la fois pour la compréhension de son parcours artistique, mais aussi et surtout pour saisir un autre regard sur l’histoire de l’art, et une vision singulière de la peinture, dessinant un appel à la peinture du singulier.

L’histoire de l’art a toujours était le fruit d’une tension entre la ressemblance et la beauté, cette dernière pouvant trahir la mimesis, et la première pouvant déprendre l’artiste de tout style. Elle a aussi était le fruit d’une tension entre la soumission à un idéal, une idéologie, une religion, une avant-garde et la simple recherche d’une vérité singulière, cette si difficile « soumission au visible ». Le Caravage était ainsi condamné par Bellori au nom de la convenance, et, plus tard, nombreux seront les artistes isolés au nom des avant-garde.

Le style est, comme un timbre de voix, nécessaire à toute création personnelle, mais ce timbre peut parfois altérer la voix au point de la fausser, et contraindre ainsi l’artiste à une recherche purement instrumentale. L’art ornemental en est l’une des voies.

Arikha considère cette forme d’idéalisme soumettant l’art à une visée, une orientation, qu’elle soit politique, philosophique ou même, comme souvent, effet de mode comme la soumission de l’appréciation sensible à l’appréciation éthique idéaliste. Or l’art ne peut se faire le reflet trompeur d’une pensée, sa particularité est de révéler l’indicible tout en l’incarnant. C’est parce que l’art est indicible qu’il peut exprimer une expérience singulière qui la sort des normes figées des images. Ces dernières sont comme des signes à déchiffrés, comme des mots à lire et comprendre ; comme un langage à interpréter et saisir. Alors que l’art, de part le regard singulier qui lui fait face, et de part la création fidèle à un instant vécu qu’il exprime, permet à cet indicible, non pas de se dire ou de se décrire mais de se ressentir.

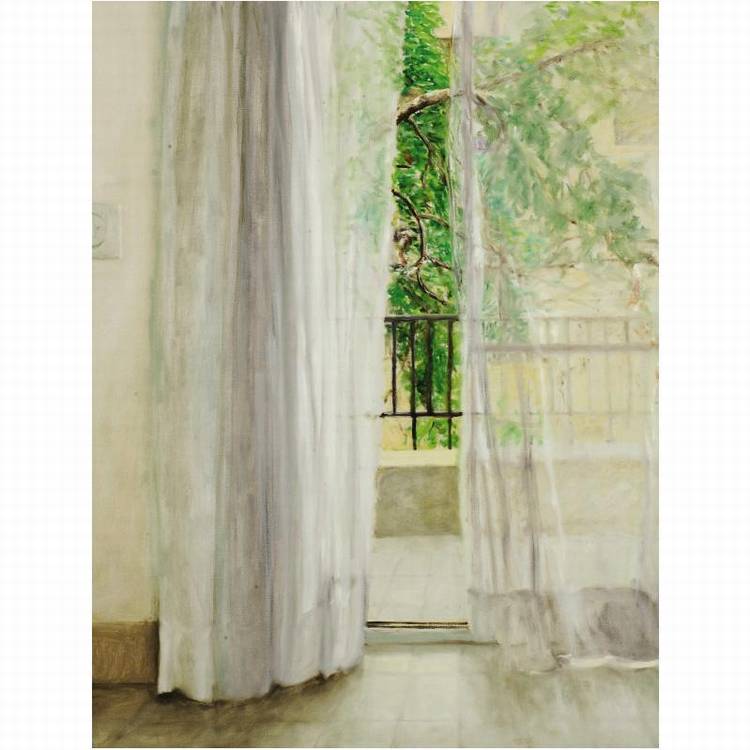

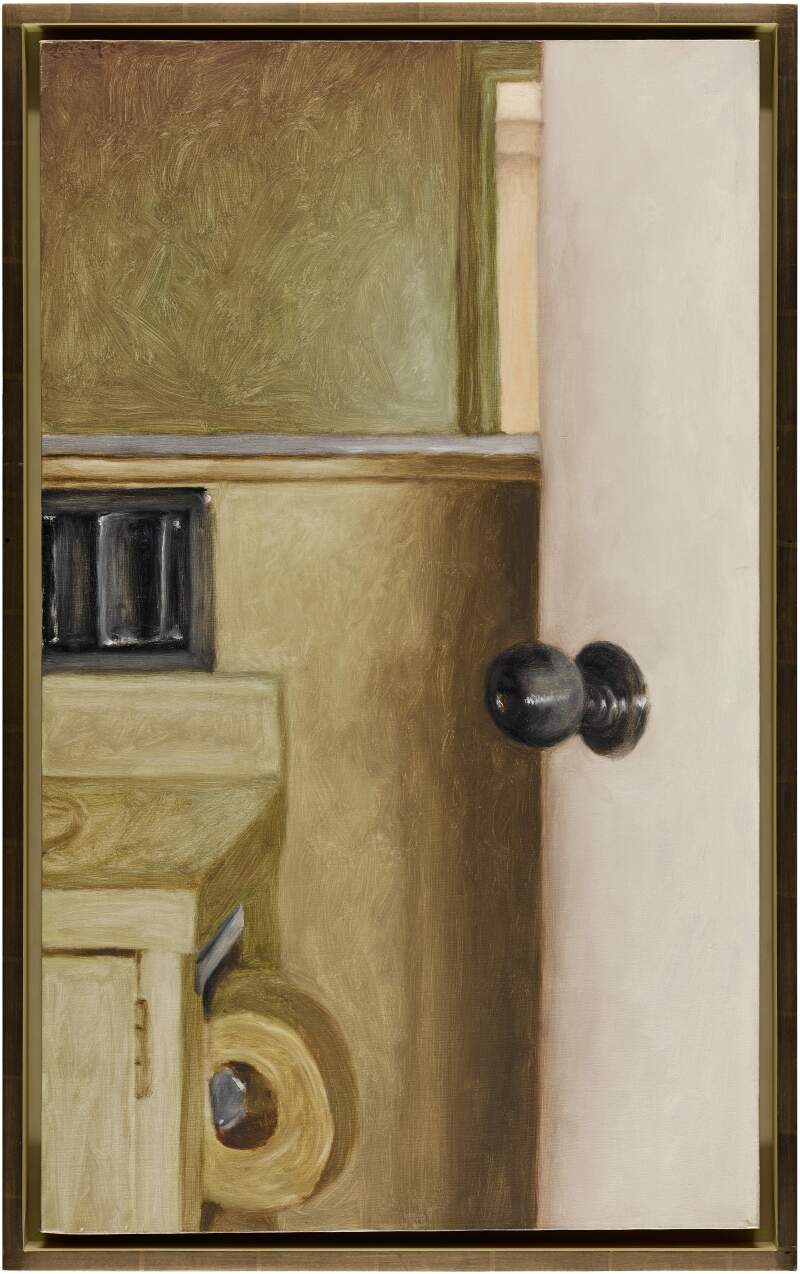

Mais, pour pouvoir ressentir l’unicité d’un vécu dans une œuvre, encore faut-il « voir justement ». Cela nécessite tout d’abord, la possibilité de voir les couleurs telles qu’elles ont été peintes, c’est-à- dire non altérées par les lumières artificielles. La lumière naturelle est un pré-requis à la captation des demi-teintes et la possibilité de regarder fidèlement une œuvre. Mais au-delà de la distorsion technique induise par la lumière artificielle, plus profondément, le regard juste nécessite d’appréhender la toile, non comme une juxtaposition d’images à décrypter, mais comme une peinture. Cette dernière se vit, et figure elle-même la trace d’un vécu. L’image se fait de mémoire, esquivant toute investigation sensible alors que la peinture est l’aboutissement de cette rencontre réalisée à vif entre le peintre et son modèle. L’imitation du typique, la soumission à une forme a priori, est cette intercession empêchant toute relation directe du sujet à son objet, et du peintre à ce qu’il cherche à retranscrire, avec toute la fidélité possible, et toute l’infidélité nécessaire.

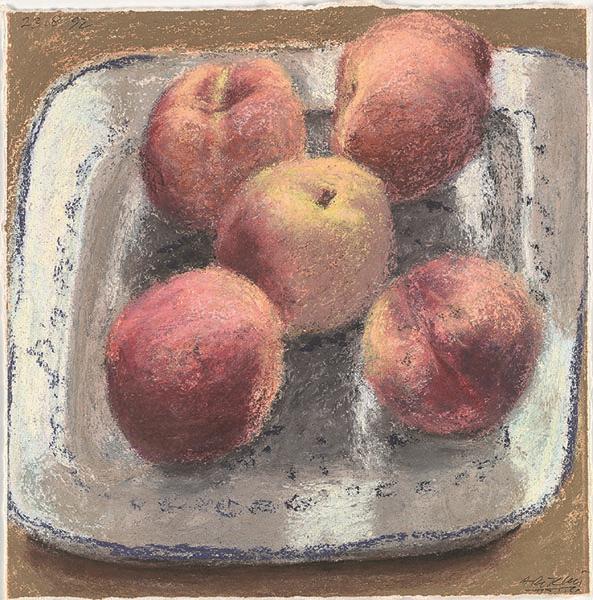

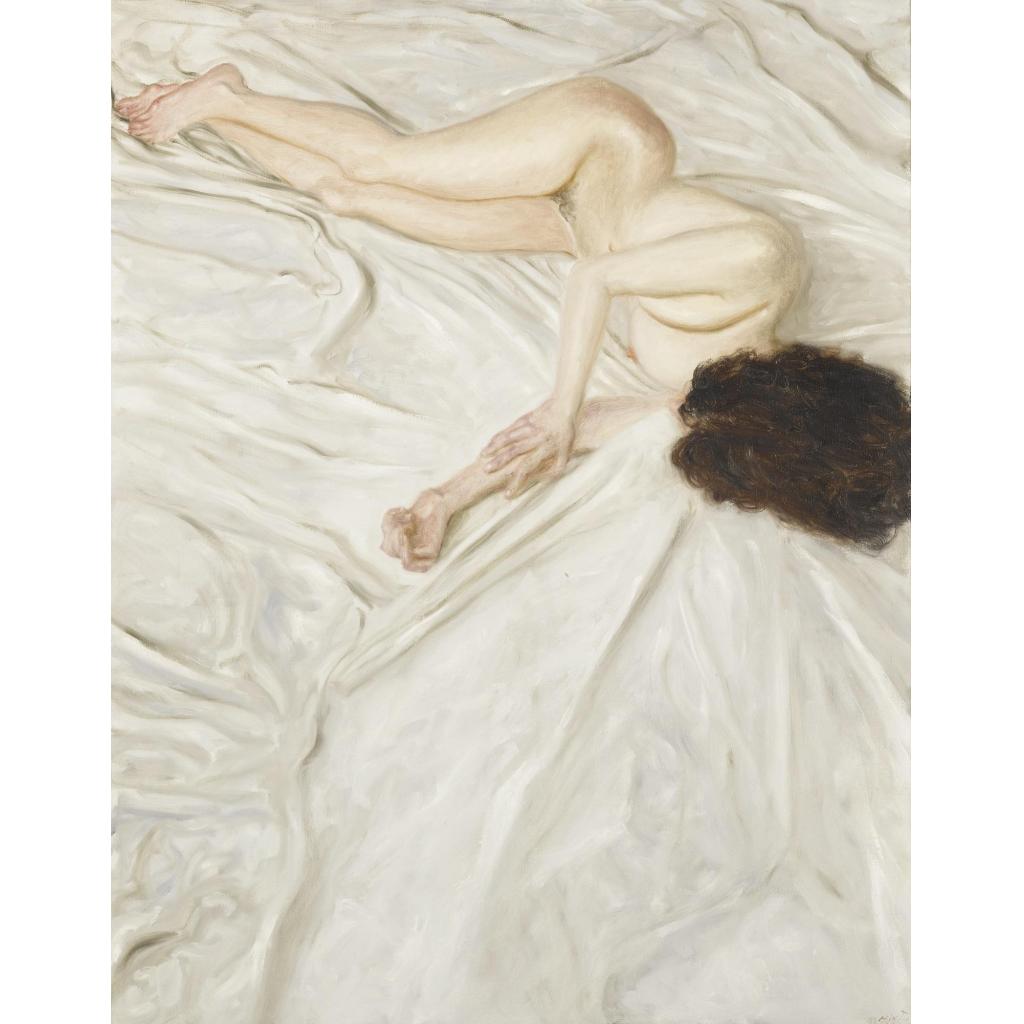

Le dessin d’observation est ainsi défendu par Arikha puisqu’il permet selon lui de « sonder, sentir et tracer, passer le senti au crible du vrai dans l’intensité sans laquelle ce qui aura été tracé ne sera que copie morte ». Cela résulte de la conjonction d’une maîtrise technique, d’où l’insistance d’Arikha pour un apprentissage rigoureux des compétences dans les écoles d’art, et, paradoxalement, d’une révocation du savoir. C’est ce trait maîtrisé, accolé à un oubli volontaire, qui permet de voir de nouveau et de tracer fidèlement. La singularité d’un visage, mais aussi d’une pomme de terre, ne peut s’absoudre dans la forme apprise et reprise ; c’est l’unicité du moment et de ce qui nous fait face que l’on doit traduire et non l’universalité de traits et de formes inculquées et répétées. Sonder, sentir et tracer est cette lutte continuelle contre le mensonge de la forme et du style intériorisé ; cela exige une immédiateté, une acuité et une sensibilité permettant au perçu de prendre le pas sur l’imaginaire, et surtout sur la mécanique implacable de la répétition.

André Breton aurait dit à Alberto Giacometti qui, en quittant le groupe surréaliste, commença par s’essayer à réaliser une tête d’après nature : « tout le monde sait ce que c’est qu’une tête ». Cette anecdote d’Arikha et son refus viscéral d’adhérer à cet oubli du visage, au profit de la tête, cet oubli de la singularité au profit de la forme, se révèle être au cœur, non seulement d’une esthétique revendiquée, mais d’une philosophie existentielle ne pouvant laisser de côté l’être, dans son irrémissible singularité.

Son parcours biographique, et les terribles affres de son enfance n’y sont sans doute pas étrangères. Arikha, révèle ainsi par sa vision de la peinture, un regard plus général où le peintre et son modèle, vivant ou éteint, ne peuvent être appréhendés comme les expressions d’une forme plus générale, mais doivent être perçus et tracées dans ce qui révèle leur unicité. Annihiler cette dernière, c’est faire de la peinture une image, c’est à dire l’échantillon visuel d’une pensée plus générale, et par sa généralisation, épouser un système anéantissant tout écho personnel.

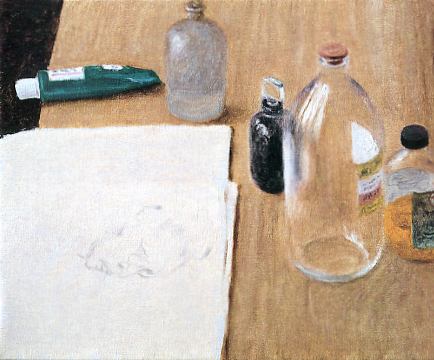

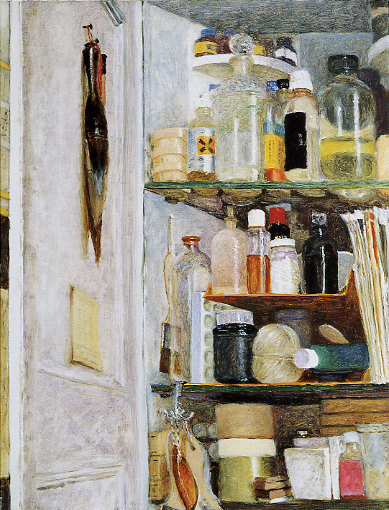

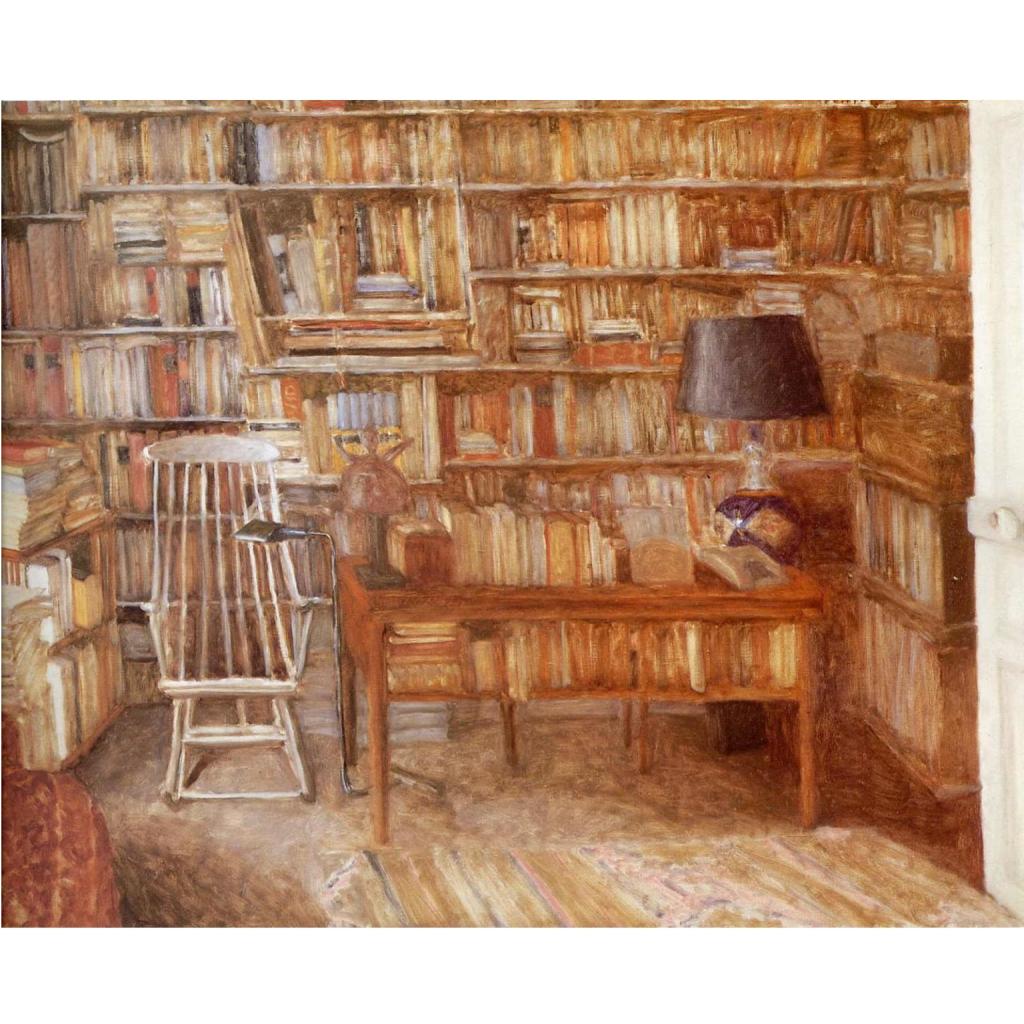

L’Assignifiant est au cœur des réflexions d’Arikha, puisqu’il refuse que l’image se substitue à la peinture, et ce refus marque l’adhésion à une conception où le concept ne se substitue pas à la fidélité. Les objets ordinaires, un flacon pharmaceutique, une baguette de pain ou une paire de souliers peuvent, lorsqu’ils sont dépeints dans leur singularité, révéler l’écho d’un moment vécu. Le distinct est ainsi préféré au distingué Les objets quotidiens dépeints expriment l’intensité de l’ordinaire et l’ordinaire de l’intensité ; Ils nous sortent de la banalité mécanique pour tenter d’appréhender cette unicité singulière ; mais cela demande voir, et voir ce que l’on voit. Plus encore, cela demande de le dépeindre fidèlement. C’est tout le paradoxe de l’unicité, elle nous fait constamment face, et elle est pourtant souvent imperceptible ; la percevoir est un art, et l’art est sous doute le fait même de le percevoir, et de le faire percevoir.

C’est toute la singularité d’Arikha que d’avoir mis en lumière l’importance même de la singularité elle-même, y compris, voire surtout, dans les moments les plus ordinaires. C’est toute sa singularité que d’avoir réussi, non seulement à l’explorer dans l’histoire de l’art, mais à la dépeindre.

Ygaël Attali

The summer theme of the Revue Eclipse is the Assignificant, hence the various interviews related to this theme and, this article on the pictorial approach and the reflections of Avigdor Arikha taken from the collection Painting and Gaze (Peinture et regard : Écrits sur l’art, 1965-2009, Paris, Éditions Hermann, 2011).

Avigdor Arikha was born in 1929 in Rădăuți in Romania and died in 2010. We know his pictorial works as well as his engravings, but his numerous writings are less known. They are rich both for the understanding of his artistic career, but also and above all for grasp another look at the history of art, and a singular vision of painting, drawing a call to painting of the singular.

The history of art has always been the result of a tension between resemblance and beauty, the latter being able to betray mimesis, and the former being able to free the artist from any style. It was also the result of a tension between submission to an ideal, an ideology, a religion, an avant-garde and the simple search for a singular truth, this so difficult “submission to the visible”. Caravaggio was thus condemned by Bellori in the name of convenience, and, later, many artists will be isolated in the name of the avant-garde.

Style is, like a tone of voice, necessary for any personal creation, but this tone can sometimes alter the voice to the point of distorting it, thus forcing the artist to purely instrumental research. Ornamental art is one of the ways.

Arikha considers this form of idealism that submits art to an aim, an orientation, be it political, philosophical or even, as often, a fashion trend, as the submission of sensitive appreciation to idealistic ethical appreciation. But art cannot be the deceptive reflection of a thought, its particularity is to reveal the unspeakable while embodying it. It is because art is unspeakable that it can express a singular experience that takes it out of the fixed standards of images. The latter are like signs to be deciphered, like words to be read and understood; as a language to be interpreted and grasped. Whereas art, through the singular gaze that faces it, and through the creation faithful to a lived moment that it expresses, allows this unspeakable, not to say or describe but to be felt.

But, in order to be able to feel the uniqueness of an experience in a work, it is still necessary to “see precisely”. This requires, first of all, the possibility of seeing the colors as they have been painted, that is to say unaltered by artificial lights. Natural light is a prerequisite for capturing halftones and the possibility of looking faithfully at a work. But beyond the technical distortion induced by artificial light, more deeply, the right gaze requires apprehending the canvas, not as a juxtaposition of images to be deciphered, but as a painting. The latter is lived, and itself represents the trace of an experience. The image is made from memory, avoiding any sensitive investigation while the painting is the culmination of this encounter made on the spot between the painter and his model. The imitation of the typical, the submission to an a priori form, is this intercession preventing any direct relation of the subject to his object, and of the painter to what he seeks to transcribe, with all the fidelity possible, and all the necessary infidelity.

Observation drawings are thus defended by Arikha since they allow, according to him, to “probe, feel and trace, to sift the feeling through the sieve of the true in the intensity without which what will have been traced will only be a dead copy“. This results from the conjunction of technical mastery, hence Arikha’s insistence on rigorous learning of skills in art schools, and, paradoxically, a revocation of knowledge. It is this mastered trait, attached to voluntary forgetfulness, which allows us to see again and to trace faithfully. The singularity of a face, but also of a potato, cannot be absolved in the form learned and taken up again; it is the uniqueness of the moment and of what faces us that we must translate and not the universality of traits and inculcated and repeated forms. To probe, to feel, and to trace is this continual struggle against the lie of form and internalized style; this requires an immediacy, acuity and sensitivity allowing the perceived to take precedence over the imaginary, and above all over the implacable mechanics of repetition.

André Breton is told to have said to Alberto Giacometti who, upon leaving the surrealist group, began by trying to create a head from life: “Everyone knows what a head is”. This anecdote of Arikha and his visceral refusal to adhere to this oblivion of the face, in favor of the head, this oblivion of the singularity in favor of the form, turns out to be at the heart, not only of a claimed aesthetic but of an existential philosophy that cannot leave aside being, in its irremissible singularity.

Arikha’s biographical journey, and the terrible horrors of his childhood are probably not unrelated. He, thus reveals through his vision of painting, a more general look where the painter and his model, alive or extinct, cannot be apprehended as expressions of a more general form, but must be perceived and traced in what reveals their uniqueness. To annihilate the latter is to make painting an image, that is to say the visual sample of a more general thought, and by its generalization, to marry a system annihilating all personal echo.

The Assignificant is at the heart of Arikha’s reflections, since he refuses that the image replaces painting, and this refusal marks the adherence to a conception where the concept does not replace fidelity. Ordinary objects, a pharmaceutical bottle, a loaf of bread or a pair of shoes can, when depicted in their singularity, reveal the echo of a lived moment. The distinct is thus preferred to the distinguished. The everyday objects depicted express the intensity of the ordinary and the ordinary of intensity. They take us out of the mechanical banality to try to apprehend this singular uniqueness, but that requires seeing, and seeing what one sees. More than that, it requires depicting it faithfully. This is the whole paradox of uniqueness, it constantly confronts us, and yet it is often imperceptible. To perceive it is an art, and art is doubtless the very fact of perceiving it, and of making it perceived.

It is all the singularity of Arikha to have highlighted the very importance of the singularity itself, including, even especially, in the most ordinary moments. It is all its singularity to have succeeded, not only in exploring it in the history of art, but in depicting it.